We all have a natural tendency to respond to various situations in different ways. Of course, that’s what makes us human. The flight or fight response is one of the body’s natural responses that occurs when triggered by a specific situation. When a person becomes scared or feels threatened, the body’s normal function amplify, helping the body prepare itself to face danger.

This phenomenon occurs rarely, so most people don’t feel ‘flight or fight’ on a regular basis. What if someone did happen to respond to most situations this way—if their body couldn’t ‘shut off’ its natural flight or fight response?

‘Flight, Fight or Learn to Cope?’

|

“Stoicism, in the modern world, can essentially help people cope with pain or hardships (emotional and physical trauma) by helping people accept the inevitable, or what has happened, without reacting in a way that’s ruled by their emotions.”

|

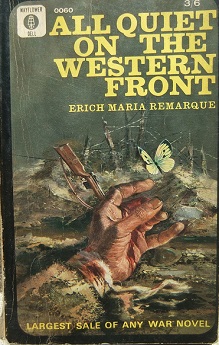

People with PTSD may feel constantly fearful or stressed even if they’re not in danger. This mental condition develops following a traumatic experience, whether the experience involved direct physical harm or a threat of physical harm. In most cases, people who develop this debilitating condition were directly involved with the traumatic experience. Some also develop the condition after experiencing several, smaller traumatic incidents.

The scary thing is that PTSD can develop in anyone who has suffered through traumatic experiences. Many people recognize this condition as something that veterans and the currently enlisted suffer through, but it also affects many civilians who have lived through extremely emotionally and physically distressing situations.

Post traumatic stress disorder is traditionally treated and managed through various types of therapy and medications. In recent times, both doctors and patients have discovered and utilized alternatives to help alleviate many serious symptoms of this debilitating condition. An unconventional, yet familiar way to treat PTSD involves changing one’s way of thinking, usually through affiliating oneself with a new religion or life philosophy.

Stoicism and Learning To Cope

Stoicism is an ancient Greek school of philosophy, originally founded in Athens by Zeno of Citium. Stoic philosophy originally taught that ‘virtue (the highest good) is primarily based on knowledge and the wise harmoniously live with divine Reason that rules nature.’ Those under Stoic philosophy ‘also remain indifferent to the variations of fortune, pleasure and pain.’

Stoicism, in the modern world, can essentially help people cope with pain or hardships (emotional and physical trauma) by helping people accept the inevitable, or what has happened, without reacting in a way that’s ruled by their emotions. The idea is that whatever happens has happened by means of forces they can’t control, and so it has no real bearing on their character.

In this way, stoicism acts as a ‘practical guide for life.’ While it helps teach people how to deftly approach situations, it also encourages people to become more mentally tough. The lessons people can learn from stoic philosophy makes it a natural philosophy for veterans and the currently enlisted to cope with their traumatic experiences.

How Does Stoicism Help Veterans Cope With PTSD?

|

“Traumatic experiences distort how people coexist with nature and society, making people act unnaturally, far away from how their true character would actually act.”

|

As mentioned, stoic philosophy has the potential to help veterans learn to cope with post traumatic stress disorder. The main way that veterans can utilize this life philosophy is learning how to flourish as a human being. According to Stoicism, the main goal of life is to flourish: to live in continued excellence, to live happily, to live with a peace of mind, to live as a strong character and to live with enthusiasm for life.

People with post traumatic stress disorder have had their cognitive functions inhibited to a point that prevents them from adopting healthier behavioral patterns. This, naturally, inhibits their ability to truly enjoy and flourish in life. PTSD forces a person to develop a type of ‘traumatic functioning,’ which puts them in a situation where they feel as if they’re stuck in a mode that prevents them from being ‘normal.’

While people don’t stay in one mode forever, many do switch between the various modes of traumatic functioning. Stoicism can help people break away from the cycle, helping them flourish as human beings again.

Character, according to stoicism, is our ability to tell apart good from evil and act upon our interpretation. How people weave themselves through nature determines their character, based on how they act on the inside. Stoicism also teaches that external elements don’t help people flourish, but it’s how people use those elements to build character if they choose.

According to stoicism, people can become harmonious once again with nature, as long as they can return to their true character. Traumatic experiences distort how people coexist with nature and society, making people act unnaturally, far away from how their true character would actually act. Stoicism helps people return to their true character by teaching them how to keep their character harmonious with nature.

Learning to Cope with Stoicism

Stoicism may help people with PTSD learn that ‘whatever occurs has happened by means of forces they can’t control, and so it has no real bearing on their character.’ For those involved in traumatic experiences related to war, stoicism can help them eventually accept the inevitability of what likely happened during their time in service and, eventually, learn how to cope.

For more information about stoicism and veterans, read this blog post: http://www.dailykos.com/story/2015/06/29/1397640/-Stoicism-for-Trauma-Survivors-Part-1

Picture: Flickr/dakine kane