When soldiers are sent to the trenches of war, amongst the necessity for their rifles, daily food rations and combat boots, there is also a necessity for them to have left their loved ones behind. No families are allowed on the front lines, for just as a man would never masturbate in front of his dear mother; neither would he commit an act of war. Those things which happen during battle are for warriors’ eyes only. But what E.M. Remarque does in his work of fiction, All Quiet on the Western Front, is to bring war to the eyes of those who have never seen it; and it is through his detailed depiction of the inner landscape of a soldier’s soul, that he gives vision to the families, and creates a truly unique work of literary fiction.

As a reader I felt more as though I were reading a man’s private journal than reading a work of fiction, for in the same way that fiction can feel more real than non-fiction, the author found a way to have his story told fully and personally. This is excellently done on E. M. Remarque’s part, because when an author writes a good book, it truly should act as a journal for the author’s character, and become a journal for the reader. A good book forces a man to convalesce into himself and write in the margins his deepest thoughts; spurred on by a word or phrase. A typical work of fiction or non-fiction hardly drives a reader to write in the margins, or to stop and pause as he ponders over a thought which has, seemingly, randomly popped into his head. The author’s greatest achievement isn’t his descriptions of the actual landscape of war, nor his political descriptions and breakdowns of the madness of war, although both are well done, his real style is in his ability to bare a man’s/character’s soul and have the reader feel as though they are reading non-fiction rather than fiction.

“We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation. It is not against men that we fling our bombs, what do we know of men in this moment when Death is hunting us down—now, for the first time in three days we can see his face, now for the first time in three days we can oppose him; we feel a mad anger. No longer do we lie helpless, waiting on the scaffold, we can destroy and kill, to save ourselves, to save ourselves and to be revenged.”

It is through detailed musings like this which we learn more about the author, the characters, and the story itself, then we could through the scenery of the trees, scenes of actual battles, or dialogue. As stated before, the author excels in all three aspects, but what truly makes his work unique is the inner, not the outer. Although, in order for the author to truly make his internal musings as powerful as he does, he sets things up by first building up the scenery of the war, “The wire entanglements are torn to pieces. Yet they offer some obstacle. We see the storm-troops coming…” deepens it with the scenes of action, “We make for the rear, pull wire cradles into the trench and leave bombs behind us with the strings pulled…”, and only then does he delve into the inner character workings and musing. “We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation…”

|

“E. M. Remarque shows us that what drives his story is the inner parts of a man.”

|

What is absent from the author’s story is any plot or typical character development. There is no arch. No one, or nothing, is keeping Paul from his true love or his goal; nor is Paul fighting for any altruistic reason, he neither seems to be fighting against any real enemy or even himself, and he fights for no reason. Paul is merely a man struggling to exist as a soldier in a war. The author fills in the blanks and the storyline with, instead of a typical hero/love plot, reflections from a young soldier as he struggles through war and ultimately ends up with nothing and no one. There is no growth. No middle. No climax. No end. No conclusion. But the story misses nothing, and through the author’s technique of internal character exploration, the story is carried on even though we have no definitive storyline to carry us through. War calls for no further subtext than a soldier trying to stay alive, and keep his sanity. There is no different war story to be told. This is what the author gives us.

A book made of such mental vivisection that if it were any more real, readers would have to be treated for PTSD.

“And this I know: all these things that now, while we are still in the war, sink down in us like a stone, after the war shall waken again, and then shall begin the disentanglement of life and death.”

“The days, the weeks, the years out here shall come back again, and our dead comrades shall then stand up again and march with us, our heads shall be clear, we shall have a purpose, and so we shall march, our dead comrades beside us, the years at the front behind us: –against whom, against whom?”

What I’ve learned from this book is that character and internal landscape is king, and combined with good scenery, good action, and good dialogue, a classic can be born. E. M. Remarque shows us that what drives his story is the inner parts of a man, but in order for that to work the scenery must be setup, then the scene itself, and then the inner musings.

For more annotative essays and other book related stuff click here.

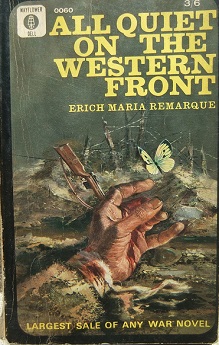

Picture: Flickr/ Gwydion M. Williams

Why We Read

Why We Read