Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir .

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir .

BookTuber “What Kamil Reads,” reviews eleven books (Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir, is the first book in the series).

Books mentioned in the video:

Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir

by Michael Anthony

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3…

Sunset Limited: A Novel in Dramatic Form

by Cormac McCarthy

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/9…

Utopia for Realists: And How We Can Get There

by Rutger Bregman

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3…

On the Suffering of the World

by Arthur Schopenhauer

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1…

MaddAddam (MaddAddam #3)

by Margaret Atwood

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1…

The Nix

by Nathan Hill

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2…

Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

by Matthew Desmond

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2…

Siddhartha

by Hermann Hesse,

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5…

Fever Dream

by Samanta Schweblin,

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3…

The Underground Railroad: Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 2017

by Colson Whitehead

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3…

The Sound and the Fury

by William Faulkner

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1…

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir

Cool News. My newest book Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir, won the 2017 Massachusetts Bay One Book Award.

Comes with a few speaking engagements, and a little money, but the coolest part is that all freshman at Mass Bay College in Fall 2017 / Spring 2018 will have to read Civilianized. They also buy copies for all faculty and staff to read and do it in conjunction with the Wellesley Free Library and get the whole town reading/enjoying it. “One Book, One Community,” type of thing.

If you’ve read the book, you’ll know that it’s dark, and a little humorous, and will definitely lead to some interesting conversations around campus and in the Wellesley community.

If you haven’t checked Civilianized out yet, definitely give it a read: Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir.

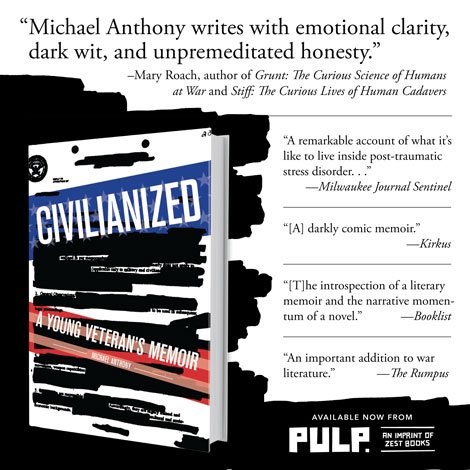

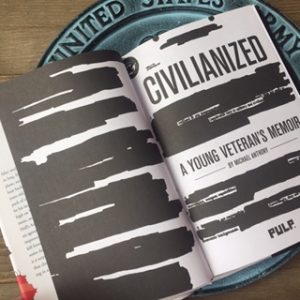

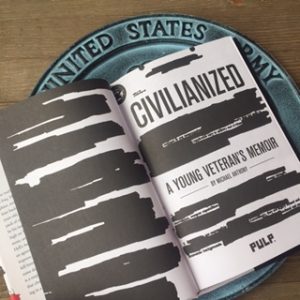

I had my wife take some promo pictures of the new book.

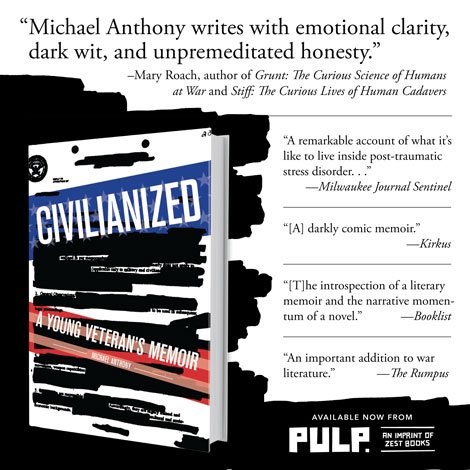

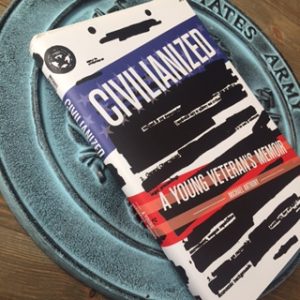

Hey Everyone! I wanted to let you know that my new book is officially for sale and available for Pre-Order.

Hey Everyone! I wanted to let you know that my new book is officially for sale and available for Pre-Order.

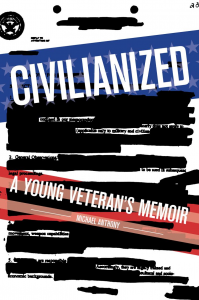

The title is: Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir. It’s a story about my homecoming from Iraq and some of the struggles I faced (though it’s a bit darker, and funnier than it might sound/seem). Here’s the text from the jacket:

“After twelve months of military service in Iraq, Michael Anthony stepped off a plane, seemingly happy to be home–or at least back on US soil. He was twenty-one years old, a bit of a nerd, and carrying a pack of cigarettes that he thought would be his last. Two weeks later, Michael was stoned on Vicodin, drinking way too much, and picking a fight with a very large Hell’s Angel. At his wit’s end, he came to an agreement with himself: If things didn’t improve in three months, he was going to kill himself. Civilianized is a memoir chronicling Michael’s search for meaning in a suddenly destabilized world.”

Pick up a copy today!

War stories continue to capture the attention of today’s generation. Stories of how veterans survived each encounter they had with the enemy, how they managed to live with the limited supplies that they had, how they met and made friends not only with their comrades but also with the locals of the place where they were deployed, and how they learned more about appreciating life through their near-death experiences continue to become fascinating windows to the past and current events.

[pullquote]”Humor is a powerful and indispensable tool in keeping one’s sanity intact in the face of death and destruction.”[/pullquote]Your grandparents or any relative who had been deployed to war may have told their war story differently. You may notice that every time your grandfather tells his story, it would be filled with details of the places he has been in, the people he has encountered, the sensations of terror and waiting for death which would scare the living hell out of anyone. Sometimes, your veteran relative would focus on his achievements in the war, such as how he managed to lead his troop into enemy camp and capture it, how he killed men, and how he was considered a hero.

It may be an attempt to recall what had happened, it may have been altered to favor the storyteller’s image as a war hero, but the common theme surrounding the telling of war stories is the use of humor — its use of jokes, of anecdotes, of words which are meant to make people feel the impact of the events in the story.

Why is humor used by war veterans to tell their war stories? Being that what they are telling is their experiences in gruesome battle, which may have been traumatizing to thousands and even millions of people at the time, what would be the reason why humor would be needed to retell these tales?

War is painful. Not only does it injure people physically, imprinting lifelong marks on the skin of soldiers and civilians, but it is also emotionally and mentally stressful to the mind and spirit. Many have gone mad just by serving in the war for a few months. Civilians who have witnessed the horrors of war experienced being in the middle of conflict and being unable to do anything about it, except just to hope that they are not killed with the guns and the bombs that are going off everywhere. If explosives are not going off, people think of how to survive with limited supplies. Of course, soldiers are usually provided with food and shelter by their government in order to survive, but in the end they would still need to use their own creativity and wits just to make it through every day without starving, going mad, or becoming thoroughly exhausted.

Being in a war is one of the most painful experiences that a person can go through in life. It changes you and makes you more aware of the horrors that lie in the world. If people continue to wallow in the pain and suffering that comes with being in a war, it would be difficult to find the courage to get up from bed every day without your conscience being bothered.

Humor is a survival tool in this instance. It helps war veterans deal with the horrors and the stresses of war, and helps make it easy to retell their war experiences. Humor acts as a pain reliever which helps veterans and civilians (who can also be considered as war veterans in their own right) keep positivity in their lives, thus encouraging them to continue living their life to the fullest.

Humor is a powerful and indispensable tool in keeping one’s sanity intact in the face of death and destruction.

Just because people have gone to war and experienced it firsthand does not mean that simply being happy is something that they should be guilty about. There is no need for anyone to wallow in the miseries of war and destruction. Even in the darkest moments, people can still laugh, see the bright side of life, continue to hope, and appreciate what life has to offer.

In this dark humored War Memoir, Iraq veteran Michael Anthony discusses his return from war and how he defeated his PTSD. Civilianized is a must read for any veteran, or anyone who knows a veteran, who has returned from war and suffered through Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“I wont soon forget this book.” -Mary Roach

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“[S]mart and mordantly funny.” –Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir .

War veterans are the ones who usually develop PTSD. This can occur while they are still working with the military or after. Thankfully, the Department of Veterans Affairs has several programs that can help retired soldiers cope up with PTSD. From diagnosing the common symptoms to intensive treatment, the VA has you covered. Moreover, they also employ numerous mental health professionals who relentlessly research on new and effective ways to help PTSD patients and their families.

In this post, you will learn more about the Department of Veterans Affairs’ PTSD treatment programs and how you can apply for help.

Every war veteran has a chance to be eligible for the VA’s PTSD services. Here are the factors that can affect your eligibility:

However, you should also take note of the following:

Thanks to the advancements in medicine and technology, veterans suffering from PTSD can choose from a variety of treatments. Below is a list of mental health treatments offered by the VA:

This one is a type of counseling method and is considered as one of the most effective methods for treating PTSD. The VA offers two types of therapies under CBT. One is the Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and the other one is Prolonged Exposure treatment.

CPT will teach you effective ways for handling any distressing thoughts that come in your head. Therapists can walk you through your previous experience (in a safe manner) and help you understand the situation better. If you know how the traumatic experience changed your outlook and behavior, it will be easier for you to cope with it.

CPT has four main processes:

Aside from frequent meetings with a mental health professional, you will also be given practice exercises that will develop your emotional and cognitive well-being, even when you’re outside the therapist’s office.

The second option for the CBT is the Exposure Therapy. As the name implies, this treatment requires the patients to be repeatedly exposed to any feelings or situations that they have been avoiding. This will teach war veterans that not everything that reminds them of a traumatic event should be avoided.

After identifying all of the situations that you commonly avoid, your therapist will require you to confront all of them until your stress levels or fears decrease.

Similar with the CPT, the Exposure Therapy also has four parts:

Exposure Therapy requires around 15 sessions with your therapist and practice assignments that you need to do on your own. As time goes by, you will be able to control your reactions when faced with stressful situations.

In this type of therapy, you will be required to focus your attention on hand gestures while you are discussing the traumatic events that triggered PTSD symptoms.

When our eyes are following fast movements, it becomes easier for our brains to process traumatic events. If you have other things to focus on while discussing these memories, your behavior will change as time goes by. It will also help that you relax and efficiently handle any emotional distress in the future.

EMDR is composed of four parts:

After the EMDR sessions, you will have a more positive outlook when recalling traumatic events in your life. It usually takes around four sessions with a therapist to see the improvements.

The treatments offered by the VA are thoroughly researched to make sure that they are effective on war veterans. However, please be reminded that the programs offered may vary per VA hospital. In some cases, the treatments may also need a referral. Your personal physician can guide you in selecting the program that suits you best.

In this dark humored War Memoir, Iraq veteran Michael Anthony discusses his return from war and how he defeated his PTSD. Civilianized is a must read for any veteran, or anyone who knows a veteran, who has returned from war and suffered through Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“I wont soon forget this book.” -Mary Roach

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“[S]mart and mordantly funny.” –Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir .

Picture: Flickr/Army Medicine

One challenge that victims of PTSD have to face is the judgment of other people due to misinformation. Because of the myths surrounding this medical condition, the relationships of the patient with his or her loved ones are often strained.

The prejudice and maltreatment of PTSD patients have been around ever since human beings started to wage wars against each other. Even though extensive research has already been conducted regarding the psychological effects of war on soldiers, there is still a lot to learn about PTSD. That is the reason why these myths are still proliferating.

So to help you better understand combat-related PTSD, here are several myths that were already debunked a long time ago:

Having PTSD means you are mentally weak

This myth is one of the oldest and most difficult to combat. Having this type of condition is not a sign of mental weakness, or even weakness of character. Aside from the internal strength of an individual, there are a lot of factors that can affect the development of PTSD. Examples of this are the type of trauma, circumstance, duration, and the number of traumatic events that happened throughout a person’s lifetime.

PTSD also occurs when the individual does not have a solid interpersonal support system. Sadly, a lot of war veterans do not get the support that they need because of social stigma and misunderstanding.

Any experience can be a traumatic one

It is true that a lot of events that happen to us can become stressful. However, there are still several criteria that need to be met before calling a certain event as “traumatic.”

The criteria are as follows:

When you say indirectly exposed, this pertains to hearing and seeing the details of the traumatizing experience. An example of this one is the drone pilots. They may not be in the middle of the warzone, but they are still exposed to the horrors of the battlefield because of the things that they see and hear on the screen. In addition, they also enter and exit the war zone regularly.

A person can easily develop PTSD after being exposed to a traumatic incident

When faced with a traumatic experience, you can expect that you will be mentally, emotionally, and physically stressed. However, it does not mean that you will already develop PTSD immediately. In order to be diagnosed with this condition, the feelings of extreme fatigue, stress, or anxiety should last for more than a month. In addition, people who suffer from PTSD also find it difficult to focus on their work and personal life.

People who suffer from PTSD are automatically crazy and extremely dangerous

Class war movies and sensationalized news reports have taught us that war veterans suffering from PTSD are crazy and should be avoided at all costs. Keep in mind that this stereotype is entirely wrong. This type of condition should never be associated with psychosis and extreme violence. PTSD is mostly about abrupt mood changes and reliving distressing memories. Never use the word crazy when talking about patients suffering from this condition because it damages their reputation and stigmatizes them further.

People with this condition are completely useless in work environments

A lot of soldiers do not want to seek treatment for PTSD because they fear that they will lose their ranks in the military. This is also the same with other workers who have developed the same condition.

Sadly, what people do not know is that they can still keep their regular jobs while getting PTSD treatments at the same time. One should not be too scared when diagnosed with this condition because it is very manageable.

PTSD is easy to get over with as time goes by

Thanks to modern PTSD treatments, it is now easier for war veterans to return to their normal lives. However, this condition does not instantly go away once you take some anti-depressants. Sometimes, conquering PTSD is a life-long journey. While most people learn to cope on their own, a lot of patients still seek professional guidance every once in a while.

War veterans who developed PTSD are not considered as part of the “wounded soldiers”

That is because you cannot see any huge scars or other types of physical injuries. However, one should remember that veterans with PTSD have made a lot of sacrifices to protect the country. Psychological injuries are quite the same with the physical ones. Both are collateral war damages that are inevitable.

You cannot do anything for war veterans (or other people) suffering from PTSD

This condition is actually very responsive to treatment. And with the advancement of medical technology, there is currently a multitude of ways to treat PTSD. If your current treatment does not work for you, you can still choose other options like cognitive behavioral therapy or prolonged exposure treatment. Seeking help from a professional is the first step in choosing an option that works best for you.

PTSD only targets a specific age group

Keep in mind that children can also experience PTSD. But as discussed in Chapter 1, their symptoms may vary depending on their age.

You only need one treatment for PTSD

Not necessarily. The type and complexity of the treatment will still depend on the person suffering from this condition. If he is showing severe symptoms, it means that he may have to undergo different types of therapies. Doctors may also ask him to take several antidepressants.

Therapies never work

Therapies are effective at treating patients because it helps them understand what PTSD is all about. It also helps health professionals to assess the patient and develop ways to help them cope with their situation. With methods such as exposure therapy and cognitive behavior therapy, people with PTSD will learn how to face their fears and deal with bad memories in a healthier and safe manner.

In this dark humored War Memoir, Iraq veteran Michael Anthony discusses his return from war and how he defeated his PTSD. Civilianized is a must read for any veteran, or anyone who knows a veteran, who has returned from war and suffered through Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

“I wont soon forget this book.” -Mary Roach

“A must read.” -Colby Buzzell

“[S]mart and mordantly funny.” –Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Anthony delivers a dose of reality that can awaken the mind…” Bookreporter

Order your copy of Civilianized: A Young Veteran’s Memoir .

Picture: Flickr/MilitaryHealth

When soldiers are sent to the trenches of war, amongst the necessity for their rifles, daily food rations and combat boots, there is also a necessity for them to have left their loved ones behind. No families are allowed on the front lines, for just as a man would never masturbate in front of his dear mother; neither would he commit an act of war. Those things which happen during battle are for warriors’ eyes only. But what E.M. Remarque does in his work of fiction, All Quiet on the Western Front, is to bring war to the eyes of those who have never seen it; and it is through his detailed depiction of the inner landscape of a soldier’s soul, that he gives vision to the families, and creates a truly unique work of literary fiction.

As a reader I felt more as though I were reading a man’s private journal than reading a work of fiction, for in the same way that fiction can feel more real than non-fiction, the author found a way to have his story told fully and personally. This is excellently done on E. M. Remarque’s part, because when an author writes a good book, it truly should act as a journal for the author’s character, and become a journal for the reader. A good book forces a man to convalesce into himself and write in the margins his deepest thoughts; spurred on by a word or phrase. A typical work of fiction or non-fiction hardly drives a reader to write in the margins, or to stop and pause as he ponders over a thought which has, seemingly, randomly popped into his head. The author’s greatest achievement isn’t his descriptions of the actual landscape of war, nor his political descriptions and breakdowns of the madness of war, although both are well done, his real style is in his ability to bare a man’s/character’s soul and have the reader feel as though they are reading non-fiction rather than fiction.

“We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation. It is not against men that we fling our bombs, what do we know of men in this moment when Death is hunting us down—now, for the first time in three days we can see his face, now for the first time in three days we can oppose him; we feel a mad anger. No longer do we lie helpless, waiting on the scaffold, we can destroy and kill, to save ourselves, to save ourselves and to be revenged.”

It is through detailed musings like this which we learn more about the author, the characters, and the story itself, then we could through the scenery of the trees, scenes of actual battles, or dialogue. As stated before, the author excels in all three aspects, but what truly makes his work unique is the inner, not the outer. Although, in order for the author to truly make his internal musings as powerful as he does, he sets things up by first building up the scenery of the war, “The wire entanglements are torn to pieces. Yet they offer some obstacle. We see the storm-troops coming…” deepens it with the scenes of action, “We make for the rear, pull wire cradles into the trench and leave bombs behind us with the strings pulled…”, and only then does he delve into the inner character workings and musing. “We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation…”

|

“E. M. Remarque shows us that what drives his story is the inner parts of a man.”

|

What is absent from the author’s story is any plot or typical character development. There is no arch. No one, or nothing, is keeping Paul from his true love or his goal; nor is Paul fighting for any altruistic reason, he neither seems to be fighting against any real enemy or even himself, and he fights for no reason. Paul is merely a man struggling to exist as a soldier in a war. The author fills in the blanks and the storyline with, instead of a typical hero/love plot, reflections from a young soldier as he struggles through war and ultimately ends up with nothing and no one. There is no growth. No middle. No climax. No end. No conclusion. But the story misses nothing, and through the author’s technique of internal character exploration, the story is carried on even though we have no definitive storyline to carry us through. War calls for no further subtext than a soldier trying to stay alive, and keep his sanity. There is no different war story to be told. This is what the author gives us.

A book made of such mental vivisection that if it were any more real, readers would have to be treated for PTSD.

“And this I know: all these things that now, while we are still in the war, sink down in us like a stone, after the war shall waken again, and then shall begin the disentanglement of life and death.”

“The days, the weeks, the years out here shall come back again, and our dead comrades shall then stand up again and march with us, our heads shall be clear, we shall have a purpose, and so we shall march, our dead comrades beside us, the years at the front behind us: –against whom, against whom?”

What I’ve learned from this book is that character and internal landscape is king, and combined with good scenery, good action, and good dialogue, a classic can be born. E. M. Remarque shows us that what drives his story is the inner parts of a man, but in order for that to work the scenery must be setup, then the scene itself, and then the inner musings.

For more annotative essays and other book related stuff click here.

Picture: Flickr/ Gwydion M. Williams

An Annotative Essay on: Cures for Hunger, by Deni Bechard

Pacing is when athletes spread out their strength and power over a period of time rather than in short bursts; longer distance runners use the technique, as well as swimmers and bicyclists. Pacing helps an athlete save themselves for the entirety of a competition/sport rather than just the beginning or end. Through pacing they’re able to spend hours giving the amorous 110% rather than just minutes or seconds—like in sprinting, etc. (Usain Bolt has no need to pace himself since he’s only running for nine seconds at a time.) But what about writers? Writers too need to pace themselves when telling a story; and the memoir Cures for Hunger by Deni Y. Bechard is a great example of literary pacing.

|

“We watch and read because we’re interested in the outcome, and it’s the pacing that keeps us going as we follow along the journey…”

|

Just as a runner can burst ahead at the beginning of a race, foreshadowing a future win, so too can a writer burst ahead at the beginning of a novel/memoir and foreshadow what’s to come. Bechard started his memoir with a prologue in which we learn that his father has died alone and in a cabin, that his father has had trouble with the law, and that the two were estranged. Then Bechard took a jump backward and began talking about his childhood, and so started the pacing; Bechard started off ahead, letting us know what the outcome was going to be, and then it was time to just sit back and watch the other 26.2 miles of the marathon.

Through the memoir, we are shown a chronological order of events that have taken place in Bechard’s life, and that of his father, Edwin. Bechard doesn’t give us too much at once, just a consistent stride throughout. Foot after foot until the race is over. That’s how it is for running, swimming and bicycling; and that’s how it is for writing, too. A writer needs to set the tone/pace that they’re going to use through their book, essay, and memoir, and it needs to be a pace that they’re comfortable with, that they can maintain, and that will ultimately, in a sense, lead them to victory! This is what interests us as readers and spectators. We become curious whether or not the person who takes the lead is actually going to win: What if an underdog comes from behind? What if the person trips? What if they win in a way that wasn’t expected? What if no one took the lead and we’re only watching to find out who eventually wins? We watch and read because we’re interested in the outcome, and it’s the pacing that keeps us going as we follow along the journey, cheering, hooting, and hollering, crying in victory and defeat, along with the winners and losers, and the characters and narrators.

|

“When someone’s running a long-distance marathon, the last thing in the world he wants to do is start sprinting right out of the gate at a speed that is unmaintainable.”

|

Bechard tells the story on his terms, letting us know right from the beginning that he’s going to be taking us through his childhood year by year. When he introduces characters he neither introduces them obtrusively nor too circumspectly. His choice of what/when to describe certain scenery/emotions is dependable in the sense that he gives us the cues so we know what to expect—the way a runner might, for instance, always tilt his head down when running up hill. He never changes his pace and gives us too much or too little at a time, it is the same consistency through the book, little by little we find more and more and step closer and closer to the end. It is a good technique; however, not all authors use this technique. Sometimes for better or worse. Some authors will jump around with their prose. One minute they’re ten years old and then next they’re thirty. One minute we’re introduced to a dozen family members and the next we’re engrossed in ten pages of internal dialogue. In the military this is called 30, 60, 90; it’s an exercise to increase your endurance. It’s where you start walking for thirty seconds, jog for sixty seconds and then sprint for ninety seconds; and then you repeat this again, and again, and again. It’s an exercise, but this, too, can be parlayed into literary terms. Bechard takes on a very clear and steady pace throughout his story. He doesn’t have any huge time jumps—I.E. he doesn’t go from ages thirteen to thirty in a matter of pages—and we are with him every step of the way. Other authors take a more 30, 60, 90 approach, where they will start off slow, work their way up, start sprinting ahead with the story and introduce a handful of new characters, slow down again and focus on just one character or plotline, and then work their way back up. They are simply different techniques that work well in different situations and with different people.

|

“As a reader, I knew from the strong start, how it was going to end…”

|

Pacing, though, I believe, is important for any writer, and by discovering this idea of literary-stride, through reading Cures for Hunger, I realized that I needed to look at my own work and see what type of pacing that I was using; or whether I was evening using pacing in the first place? Was I just blindly running down the road taking stops whenever tired, or was I pacing myself with something that’s comfortable, something the reader could follow along with and would be interested in, something I could maintain and enjoy? When someone’s running a long-distance marathon, the last thing in the world he wants to do is start sprinting right out of the gate at a speed that is unmaintainable. He’ll become tired, winded, and unable to complete the race. In writing, one of the worst things a piece can do is start off strong and then let the reader down the more it drags on, getting slower and slower until finally the book is put down, unfinished. But, then again, there is a need to start off strong. Not too many runners, if any, can go from a last place start to a first place win. In writing we need to start off our pieces strong, but not too strong if unable to deliver that intensity throughout. The start needs to set the pace for the rest of the book: how it will be told, what it will be about, and how things will unfold. We need to see strength right from the beginning, but it cannot be overused or unmaintainable.

Now, granted, the literary pacing/athletic pacing analogy might be a little far-stretched but, in a general sense, it works. As I read Cures for Hunger, the strong start of the prologue is what initially hooked my interest. The foreshadowing of things to come interested me in seeing how things were going to unfold and come about. Then, as the story carried on further and he took us through the years, slowly giving us pieces of the puzzle, we learned more and more, until finally the end of the book. As a reader, I knew from the strong start, how it was going to end, but the pacing of the story, and having things unfold, is what kept me interested, even though I already knew the ending. There are different ways of doing this, and I’m tepid in the idea of using it in my own current work, but it was interesting to have in mind while reading Bechard’s work. Without the prologue, I don’t believe I would have been as interested, initially, in the book. If I didn’t know what the story was going to be about, and I just started reading about someone’s childhood, then I wouldn’t have been interested. But the prologue let me know that it wasn’t just a normal childhood I’d be reading about, it was a childhood of abandonment, of adventure, of estrangement, and that ended with the death of Bechard’s father. Prologue foreshadowing is only one technique, and even though I’m not sure whether I’ll be using it on my current work, the idea of it, and of pacing, in general, I will surely keep with me throughout all future work.

For more annotative essays and other book related stuff click here.

Picture: Flickr/Doran