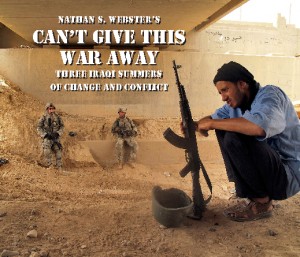

The following is an interview with Nathan S. Webster. Nathan is an Army veteran and served in the first Iraq war. He was a journalist during the second Iraq war and was embedded with the 1st/505th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 82nd Airborne Division. He’s got an amazing story to tell and chapters from his war memoir are available on amazon.com: Can’t Give This War Away

The following is an interview with Nathan S. Webster. Nathan is an Army veteran and served in the first Iraq war. He was a journalist during the second Iraq war and was embedded with the 1st/505th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 82nd Airborne Division. He’s got an amazing story to tell and chapters from his war memoir are available on amazon.com: Can’t Give This War Away

Q: When I think about the difference between the soldiers and journalists in Iraq, I think of it as the difference between an eagle and an ant. The ants live in the dirt, eat it, and sleep in it, and although the eagles don’t know what it’s like to eat in or sleep in

dirt, they see it from an entirely different perspective and they see all the dirt for miles.

Alright, stupid analogy, but you get the point, and in Iraq since you were a former soldier, veteran of Gulf War I and a journalist, you pretty much got both perspectives. So the first question that comes to mind is: how do you think being a veteran made you different from the other journalists over there? Good/bad?

A: Definitely different in a good way. Not, it’s important to note, in how the soldiers responded to me. They didn’t care that I was in Desert Storm anymore than I would have cared if somebody had told me they were in Vietnam. But, from perspective, I didn’t have to spend a lot of time getting familiar with the language they were speaking. I knew what was going on, what they were trying to accomplish, and if I didn’t always understand an acronym or nomenclature, I usually understood the context, and from that I could figure it out. Basically, I could relate to the situation a lot better, I think, than an average civilian journalist could have. Obviously, there are defense reporters with years of experience, and I don’t mean better than them. But, to be basically dropped off at a Joint Security Station in the middle of a city with little/no warmup or explanation, yeah, it helped to have a base of knowledge to draw from, whether it was 17 years before or not. I remembered pretty quick. But like one of the guys told me, “Be careful. It isn’t 1991 anymore.”

Q: Since you served during Desert Storm, how do think the press covered the lead up and aftermath of that war, compared to its coverage of Operation Iraqi Freedom? Did you have any personal experiences with journalists during your deployment?

A: They kept a tight leash on journalists during Desert Storm, and that led to people not having any clue about what actually went on. Nobody knows anything about the “Right Hook” or whatever the VII Corps offensive was called. And that’s the military’s fault – they kept most reporters in the rear, and the ground war ended so quickly there was no chance to actually report on any of it. So it’s a lot of stories lost to history. So the embedded system of this war has its critics, and there’s legit criticism that can be made, but it’s still a better system than what we had, which were paranoid PAOs keeping reporters on tight leashes with mandatory escorts, a bunch of glad-handing briefings, etc.

I met one journalist in Desert Storm – an English photographer who took some shots of me while I was doing laundry in a bucket. We were in Saudi at the time waiting to push north. He asked me something like “looking forward to getting this started?” and I was a typical snotty 22-year-old, and I said something like “I don’t know what you mean. Go where? Start what?” I don’t even remember, but he just rolled his eyes and said, “okay, if you say so.”

Which is almost exactly what I said in 2007 to a few guys who played the tough guy/fake ignorant act with me. I was thinking, “Whatever dude. I’m just making small talk. These aren’t the D-Day plans.” And I’m sure that’s what the photographer was thinking talking to me…

Q: I read your book “Can’t Give This War Away,” (Great book) and you tell a lot of stories about the soldiers that you were with over there and it seemed like you got pretty friendly with some of them, so I’m going to ask you the question that my mother always asks me, “Do you still talk to the friends you made while in Iraq?”

A: Plenty of them. I think they appreciated that I said I was planning to write soldier-centered stories that I would try to get published in their hometown newspaper – and when I got back, I wrote a bunch of soldier-centered stories that got published in their hometown newspapers. So I did what I said I would, and didn’t use their words against them, or go in with an agenda of my own. If I saw it or heard it, it was fair game…but I didn’t write about rumors or the usual bellyaching – of which there was plenty. But if I had no first-hand knowledge of it, I wasn’t going to go down the rumor road.

A lot of the guys have bought copies of the book, and for that reason alone I’m glad I put it together. Both commanders liked it – and while part of me thinks maybe that means it’s too sugarcoated, I know that’s not the case. It’s honest, and straightforward. I could have juiced it up if I’d wanted, with rumor and heresay and melodrama – and the first draft did that quite a bit, but that would not have been honest.

It’s not a surprise that the soldiers in 2007 and 2008 were more connected to my work…stakes were lot higher in those years. 2009 was quiet, in a good way, but it was not the same dynamic.

But, I was with the same unit in 2007 and 2009 – and those soldiers I met twice were excited/amused to see me again. So on Facebook I keep in touch with some. But, it’s a limited friendship. I’m twice their age, after all.

If you read the book, I think you can figure out who I got along the best with. There were some guys who were unimpressed with me in 2007, but they warmed up in 2009, once I’d earned some credibility.

Q: A lot of journalist go to Iraq and they embed themselves deep within some of the military units and they experience a lot of the same stresses that the soldiers do—being away from home, being in a warzone, coming close to death, seeing people dying, etc. But there seems to be no coverage, or reports, about journalists getting PTSD. Do you think it’s because journalists don’t get PTSD or is there something else going on? How was it for you when you first returned home from the war?

A: I don’t have PTSD, but I do know that late into that first year (07) whenever a door would slam in the hallway below my office, there was an instant where I didn’t think it sounded like a mortar, but that it actually was a mortar. The feeling was less than a second, barely a register in my mind, but it was there and it was involuntary. So if you extrapolate that, and magnify it by guys who were there 15 months and who were attacked every other day, like in Bayji, then it’s a wonder anybody doesn’t have PTSD. So while I don’t think I have any PTSD myself, it’s not hard for me to see how it could become that.

So, I’m sure journalists absolutely get PTSD. But, since they’re the ones doing the reporting, they’re probably not going to report on themselves. Ashley Gilbertson wrote about in “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot,” and Dexter Filkins touched on it in “The Forever War.” Basically, when you read about hard-drinking war correspondents, you’re reading about guys dealing with PTSD. Just like soldiers are conditioned to pretend it doesn’t exist, I’m sure journalists are the same.

Q: From personal experiences we both know that war can change people, whether it’s mentally, emotionally, or just politically. How do you think experiencing the war has changed you?

A: It changed everything. I went from being just one more clown bellyaching on the sidelines, to somebody with a legitimate personal investment. Granted, I was a veteran, but of Desert Storm? Come on. Comparing Desert Storm (my version, anyway) to Iraq in 2007 is like comparing the moon landing to camping in your backyard. So all the things that were academic, and reported through the media’s news filter, all of sudden became real in a way that doesn’t ever go away. My book’s last paragraph makes note of an airplane’s vapor trail – that’s a true story. Iraq’s the first thing I think of when I see that, and it doesn’t go away. It won’t ever go away. So you could say it woke me up.

On the other hand, you want something like that to have an automatic and change everything…but it doesn’t. Yeah, I almost got killed one time – but I don’t live my life any different. You might think you will, but you won’t. In the end, you’ll be who you are, and the events just give your life some color, but they don’t really change you. And, it’s been three years since I’ve been there – so part of me thinks it’s time to move on…but I wrote this book, and I want to do my best to see it published in some form. The title of the book is inspired by a song’s lyric, and while I won’t reveal the song title, one of the other lyrics is “It’s been half a month, and the media’s gone. An entertaining scandal broke, but I can’t move on.” And I guess that’s pretty true. So the title of my book answers your question.

For more great information from Nathan check out his website: Here.

I tend to not be a fan of embeds after having run into a few of them over there but this guy seems all right and they must have liked him enought to bring him back twice.

it all depends on the person. I’ve met a few really great embeds and a few really crap ones that make you wonder how they ever got approval to join us. it depends on what they’re willing to do too. some of them live off in private barracks away from us and then only come and interview a few hours a day and then call it a day. others actually go out with the guys and see what its really like.

He says that he became friends with some of the soldiers but I thought that’s exactly what a journalist didn’t want to do?

For that article in rolling stone about Stanley McCrystal it would never have gotten written had the journalist become good friends with the people involved.

That’s the trick, isn’t it?

I think I had an agenda going in – tell stories for hometown newspapers. I was not going to be interviewing higher levels officers, like McChrystal or Petraeus, so my focus was “this is a day in the life of a soldier,” and the grind, frustration, etc.

My stories were neither positive or negative – they were just honest, and I think the soldiers liked that.

One of my pictures got someone in trouble – he was wearing an “Infidel” tab above his “airborne” tab. So when the picture ran on the front page of his newspaper, somebody called somebody and he had to stand tall before the man.

But it’s not my job to tell a grown man how to dress. It was a good picture. I felt bad that he got chewed out – but not that bad.

And like his friends said, when I was with that unit again in 2009, “you didn’t get him in trouble, HE got himself in trouble.”

So as long as a journalist is honest, that’s what these guys respected, at least as far as I could tell.

When I say I’m ‘friends,’ I’m “Facebook Friends,” so it’s not a close relationship – more like a “hey, glad you’re doing well!” But it was a rough time and I’m glad I was able to share a little of it with them.

Hey Nathan, I know this is old, but many of us are trying to purchase your “Can’t give this war away book.” And none of us can find it anywhere.

Also, you’re right about Michael Hastings, author of The Operators, which is a great book.

Had he allowed any “friendship” to get in his way, he would not have done his job. So he did what he had to do, and burned all the bridges.

I’m with Nathan. As a former vet I’m sure that he was able to fit in better than the other journalists–think of Bing West, he’s a former vet and journalist and he’s taken dozens of trips overseas, and he has become friends with a lot of the troops that he writes about.

Plus to write the story, you’ve got to put yourself out there and interact. If you’re just some object in the background who no one likes or wants to talk to, then you’re going to miss a lot of the story and happenings that are going on.

I don’t think being friends stops you from writing a true story, and often it can actually help.

As the mother of two soldiers that have been sent overseas to Iraq I know what it’s like to see your child come home with PTSD, and I meet up and talk with a lot of mothers of soldiers who have been and are going overseas, but I never thought about the mothers of war correspondents. Good point to bring up Michael.